Archaeologist Volker Heyd is bringing his ERC Advanced Grant to Helsinki. So has proudly reported the University of Helskinki.

Some interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

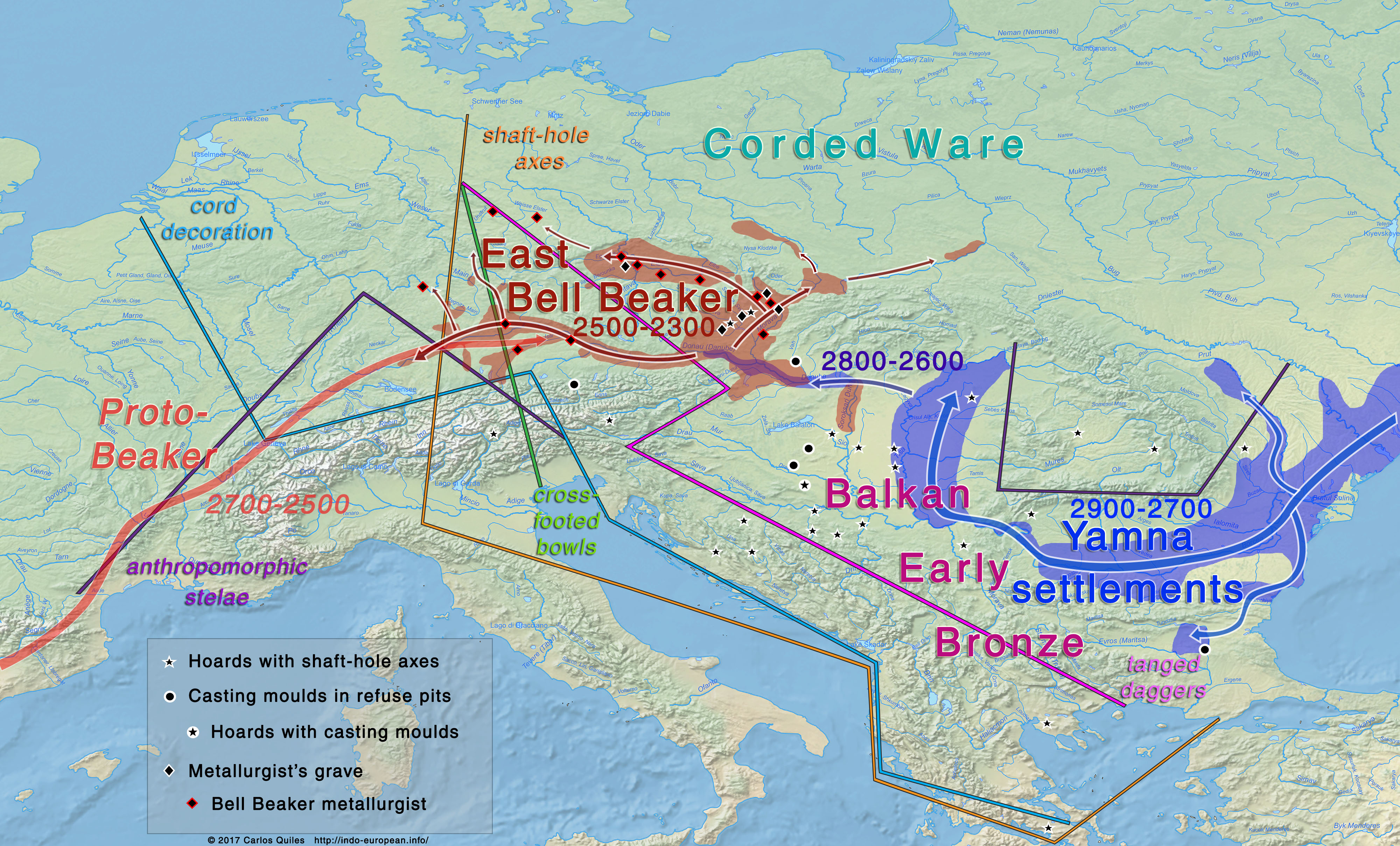

With his research group, Heyd wants to map out how the Yamnaya culture, also known as the Pit Grave culture, migrated from the Eurasian steppes to prehistoric south-eastern Europe approximately 3,000 years BCE. Most of the burial mounds typical of the Yamnaya culture have already been destroyed, but new techniques enable their identification and study.

The project is using multidisciplinary methods to solve the mystery. Archaeologists are collaborating with scholars of biological and environmental sciences, using the methods of funerary archaeology, landscape archaeology and remote sensing that are at the group’s disposal. From the field of biological sciences, the group is making use of genetics/DNA analysis, biological anthropology and biogeochemistry. As for environmental sciences, their contribution is in the form of palaeoclimatology, which studies climate before modern meteorological observations, and soil formation processes.

The project, coordinated by the discipline of archaeology at the University of Helsinki, will also welcome researchers from Mainz, London, Bristol and Budapest, in addition to which the group will collaborate with Czech, Slovak and Polish colleagues. Field studies and sample collection for the project will be conducted in Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Serbia.

In Helsinki, Volker Heyd’s main collaborator is Professor Heikki Seppä from the Department of Geosciences and Geography on the Kumpula Campus, while the team will also be hiring three postdoctoral researchers.

Yamnaya from the east changed Europe forever

The researchers wish to understand how the Yamnaya migrated to Europe and how the arrival of a new culture changed an entire continent.

How many people actually arrived? Taking the scale of the changes, some estimates range in the millions, but according to Volker Heyd, the number of people representing the Yamnaya culture in southeast Europe was around several ten thousands. It is indeed remarkable how such a relatively small group of people has had such a significant and far-reaching impact on Europe.

The Yamnaya also brought with them new cultural and social norms that have had far-reaching consequences. For instance, patriarchy and monogamy seems to be part of the Yamnaya legacy. Another established theory speculates that marriages made women migrate and travel even across great distances.

In accordance with primogeniture, the first-born son of the family inherited his parents’ possessions, while the younger siblings had to make their own way through other means. Among other things, this practice guaranteed ample human resources for the legions of the Roman Empire, which enabled its establishment and expansion, and later filled the ranks of medieval monasteries across Europe.

Another interesting question is what made representatives of the Yamnaya culture migrate from the eastern European steppes to the west. Heyd believes that the underlying reason may have been climate change. The Yamnaya were almost exclusively dependent on animal husbandry. As the climate changed – when rainfalls decreased in the east – they may have been forced to migrate west to secure the welfare of their cattle.

North-East Europe and Corded Ware

Heyd has already been here as a visiting professor in the Helsinki University Humanities programme since the beginning of the year, working on another project. Together with Postdoctoral Researcher Kerkko Nordqvist, he is investigating the prehistoric settlement of north-eastern Europe 3,000 – 6,000 years ago with research methods similar to the new Yamnaya project. One of their central research questions is what made people migrate to this region, and which innovations they brought with them. In this case also, the reasons behind the migration may be related to changes in the environment and climate.

This is probably bad news for research in the UK (I say probably because I guess many Brexiteers will be happy to have less foreign researchers in their country), but it is great news to see both researchers, Heyd and Nordqvist (whose Ph.D. thesis includes research on the Corded Ware culture that I have recently mentioned) – , be able to collaborate together to assess Indo-European and Uralic migrations.

Heyd’s website at the University of Bristol states that he is currently working on:

- ‘The Milking Revolution in Temperate Neolithic Europe (NeoMilk)‘. Funded by an ERC Advanced Grant, European Union, to R. Evershed. See, for further information: www.neomilk-erc.eu

- ‘The Yamnaya Impact‘: Archaeology and scientific research of/into the Yamnaya populations of Southeastern Europe and their impact on contemporary local and neighboring 3rd millennium BC societies as well as their role in the emergence of the Corded Ware and Bell Beaker complexes in Europe.

- ‘The Prehistoric Peopling of Northeastern Europe‘: Inter-/crossdisciplinary studies on the archaeology, anthropology, linguistics, and bio- and environmental sciences of early Uralic speakers and their first horizon of interactions with Indo-European speakers. This wider project is in cooperation with colleagues from Helsinki and Turku Universities in Finland, as well as from Russia, Estonia and Poland.

- ‘Czech Republic‘: I am closely cooperating with the Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences, in Prague for two research projects funded by the Czech Grant Agency in which we measure various isotopes from human remains in Bristol to understand past mobility and diet. The Humboldt-Kolleg -conference ‘Reinecke’s Heritage’ (with P. Pavúk, M. Ernée and J. Peska) held in June 2017 at Chateau Křtiny/Moravia is also part of this cooperation. See, for further information: http://ukar.ff.cuni.cz/reinecke.

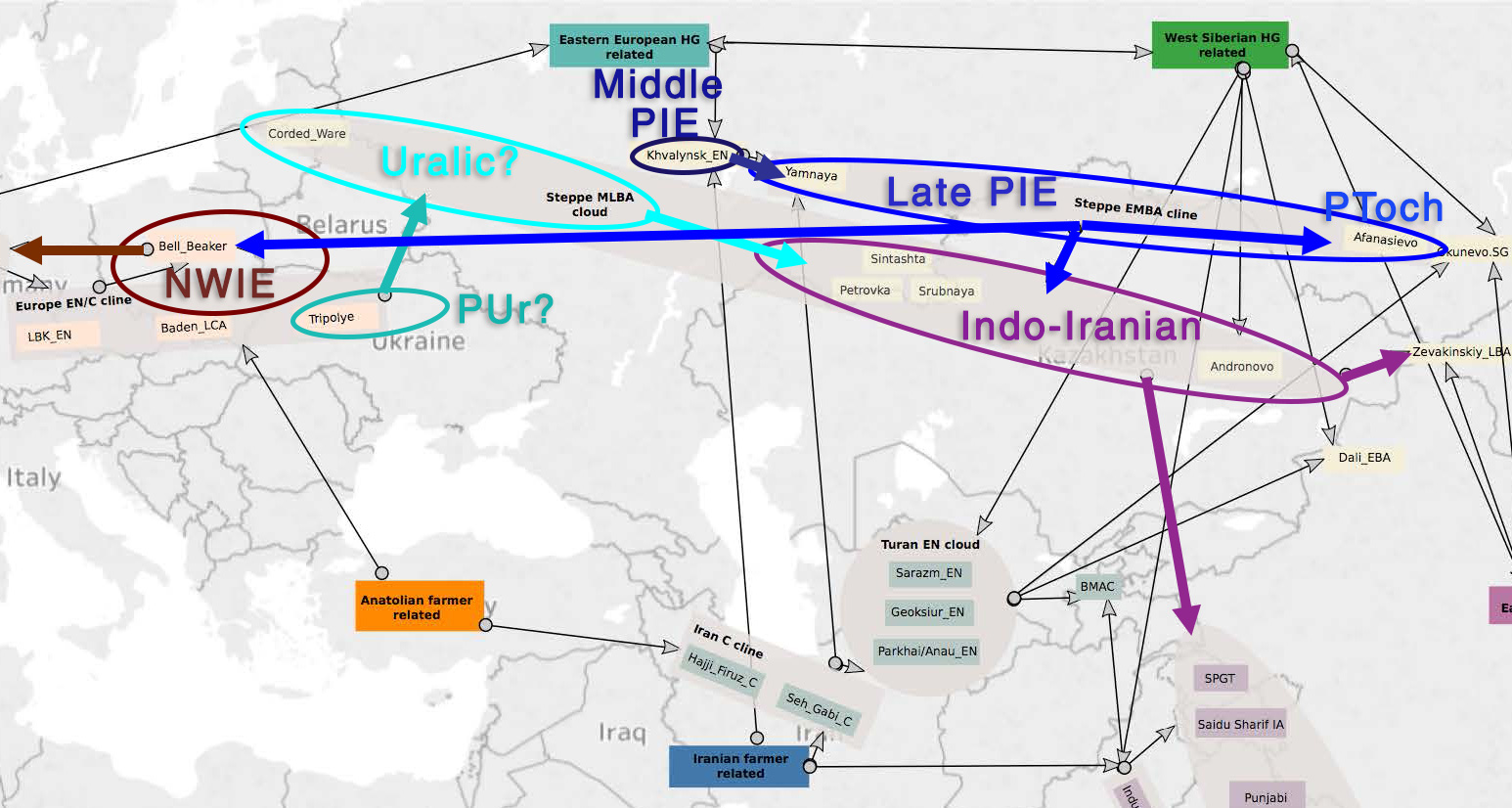

On the genetic aspect, we have gross Yamna migrations today as clearly depicted as they will ever be: late Khvalynsk/Yamna expanded Late Proto-Indo-European languages, and Bell Beakers brought North-West Indo-European to almost all of Europe, as predicted in Harrison and Heyd (2007). Full stop.

There is still fine-grained population structure, though, as Lazaridis puts it, to be detected in migratory movements contemporary or subsequent to the Yamna settlements in South-East Europe and the East Bell Beaker expansion.

We will probably lack a comprehensive description of local archaeological cultural exchanges – to fit the potential dialectal developments and expansions – to be coupled with small-scale migratory movements in genetics, as more samples are made available.

This work from the University of Helsinki will hopefully provide the necessary detailed anthropological foundations to be used with future genetic studies to obtain a more precise picture of the formation and expansion of North-West Indo-Europeans.

Related:

- Olalde et al. and Mathieson et al. (Nature 2018): R1b-L23 dominates Bell Beaker and Yamna, R1a-M417 resurges in East-Central Europe during the Bronze Age

- The Indo-European demic diffusion model, and the “R1b – Indo-European” association

- Haplogroup R1b-L51 in Khvalynsk samples from the Samara region dated ca. 4250-4000 BC

- David Reich on social inequality and Yamna expansion with few Y-DNA subclades

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (III): The Balto-Slavic conundrum in Linguistics, Archaeology, and Genetics

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (I): The latest West Yamna “outlier”

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- Heyd, Mallory, and Prescott were right about Bell Beakers