New open access paper Four millennia of Iberian biomolecular prehistory illustrate the impact of prehistoric migrations at the far end of Eurasia, by Valdiosera, Günther, Vera-Rodríguez, et al. PNAS (2018) published ahead of print.

Abstract (emphasis mine)

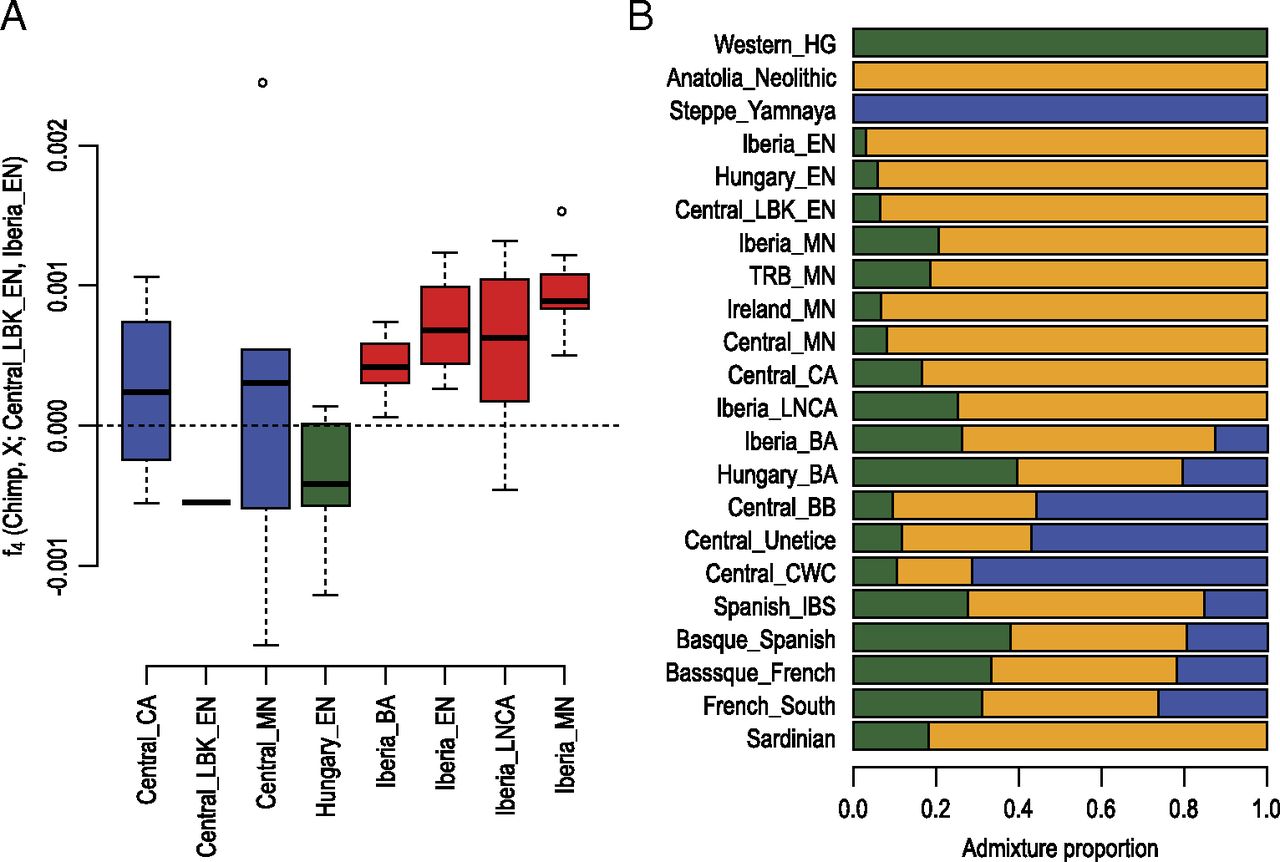

Population genomic studies of ancient human remains have shown how modern-day European population structure has been shaped by a number of prehistoric migrations. The Neolithization of Europe has been associated with large-scale migrations from Anatolia, which was followed by migrations of herders from the Pontic steppe at the onset of the Bronze Age. Southwestern Europe was one of the last parts of the continent reached by these migrations, and modern-day populations from this region show intriguing similarities to the initial Neolithic migrants. Partly due to climatic conditions that are unfavorable for DNA preservation, regional studies on the Mediterranean remain challenging. Here, we present genome-wide sequence data from 13 individuals combined with stable isotope analysis from the north and south of Iberia covering a four-millennial temporal transect (7,500–3,500 BP). Early Iberian farmers and Early Central European farmers exhibit significant genetic differences, suggesting two independent fronts of the Neolithic expansion. The first Neolithic migrants that arrived in Iberia had low levels of genetic diversity, potentially reflecting a small number of individuals; this diversity gradually increased over time from mixing with local hunter-gatherers and potential population expansion. The impact of post-Neolithic migrations on Iberia was much smaller than for the rest of the continent, showing little external influence from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. Paleodietary reconstruction shows that these populations have a remarkable degree of dietary homogeneity across space and time, suggesting a strong reliance on terrestrial food resources despite changing culture and genetic make-up.

Conclusion:

We present a comprehensive biomolecular dataset spanning four millennia of prehistory across the whole Iberian Peninsula. Our results highlight the power of archaeogenomic studies focusing on specific regions and covering a temporal transect. The 4,000 y of prehistory in Iberia were shaped by major chronological changes but with little geographic substructure within the Peninsula. The subtle but clear genetic differences between early Neolithic Iberian farmers and early Neolithic central European farmers point toward two independent migrations, potentially originating from two slightly different source populations. These populations followed different routes, one along the Mediterranean coast, giving rise to early Neolithic Iberian farmers, and one via mainland Europe forming early Neolithic central European farmers. This directly links all Neolithic Iberians with the first migrants that arrived with the initial Mediterranean Neolithic wave of expansion. These Iberians mixed with local hunter-gatherers (but maintained farming/pastoral subsistence strategies, i.e., diet), leading to a recovery from the loss of genetic diversity emerging from the initial migration founder bottleneck. Only after the spread of Bell Beaker pottery did steppe-related ancestry arrive in Iberia, where it had smaller contributions to the population compared with the impact that it had in central Europe. This implies that the two prehistoric migrations causing major population turnovers in central Europe had differential effects at the southwestern edge of their distribution: The Neolithic migrations caused substantial changes in the Iberian gene pool (the introduction of agriculture by farmers) (6, 9, 11, 13, 24), whereas the impact of Bronze Age migrations (Yamnaya) was significantly smaller in Iberia than in north-central Europe (24). The post-Neolithic prehistory of Iberia is generally characterized by interactions between residents rather than by migrations from other parts of Europe, resulting in relative genetic continuity, while most other regions were subject to major genetic turnovers after the Neolithic (4, 6, 7, 9, 25, 48). Although Iberian populations represent the furthest wave of Neolithic expansion in the westernmost Mediterranean, the subsequent populations maintain a surprisingly high genetic legacy of the original pioneer farming migrants from the east compared with their central European counterparts. This counterintuitive result emphasizes the importance of in-depth diachronic studies in all parts of the continent.

Related:

- Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula

- Population substructure in Iberia, highest in the north-west territory (to appear in Nature)

- Analysis of R1b-DF27 haplogroups in modern populations adds new information that contrasts with ‘steppe admixture’ results

- Migrations painted by Irish and Scottish genetic clusters, and their relationship with British and European ones

- Y-DNA relevant in the postgenomic era, mtDNA study of Iron Age Italic population, and reconstructing the genetic history of Italians

- The Tollense Valley battlefield: the North European ‘Trojan war’ that hints to western Balto-Slavic origins

- Olalde et al. and Mathieson et al. (Nature 2018): R1b-L23 dominates Bell Beaker and Yamna, R1a-M417 resurges in East-Central Europe during the Bronze Age